As humankind shuffles ever closer to the jaws of the global death-machine, all the magic seems to have gone out of our lives and our thinking.

Reduced to mere units of “human capital” by the usurious slave-masters, hypnotised into dull passivity by their weapons of mass distraction, too many people appear to have no ideas of their own to express and no words of their own with which to express them.

That is why it is so refreshing to have encountered the writing of Ludwig Klages, the beyond-left-and-right critic of modernity whom I described in my last essay.

Not only does he not speak the language of the industrial system, but he does not even use its syntax, to use Guy Debord’s terms. [1]

Take this passage for example:

“What in a moment of grace touches a chord in us from nature or from the works of the spring-spirits with a daimonic force is not something intellectually devised and constructed in the imagination, rather it is – born“. [2]

Or this one:

“It matters little to know if life reaches beyond the sphere of individuals or not, if the Earth, as the ancients liked to believe, is a living being or whether, as the moderns maintain, it is an inert heap of ‘dead matter’; for one thing is clear and this is that, whatever the landscape, the play of the clouds, the water, the profusion of plants and the bustle of the creatures produce a profoundly moving Whole which embraces individuals as if within an arch, embodies them by weaving them into the great cosmic becoming”. [3]

Because Klages’s philosophy stands so firmly outside the enclosure of modern thinking, it can be difficult to understand and to label.

His overall vision includes graphology – the study of handwriting – and psychology, while his life philosophy, a phenomenology he calls “the science of essences” – Wesenswissenschaft [4] is variously termed “biocentrism” and “panvitalism”. [5]

Klages deliberately cultivates what Nitzan Lebovic calls a “mythic, highly codified language”, in which he tries to reintroduce deep meaning “extricated from the ancient roots of language itself, before it was classified and organized in modern life”. [6]

This idiosyncratic use of certain terms can cause initial confusion – I was surprised, for instance, to see that he attributes negative quality to the word “spirit” – “Geist” in German – to which I, like Gustav Landauer, [7] have always attributed a very positive value.

But further investigation reveals that what he means by “spirit” is what Paul Bishop calls “objectivizing intellect” [8] or what Klages himself describes as “the enslavement of life under the yoke of concepts”. [9]

It could be seen as the rational mind, the ego, patriarchy, materialism, the will to power behind the industrial world.

Bishop says that Klages felt our civilisation had gone wrong by having “an exclusive focus on rationality instead of a richer and more holistic approach to life”. [10]

And Lebovic explains that he turned the term “logocentrism”, a focus on words rather than the reality behind them, into “a popular term hurled against all transparent Western forms of positivist analysis, patriarchalism, and materialism”. [11]

In his writing, Klages judges that our “vital plenitude” [12] is being sucked from us by contemporary society.

He sees body and soul as being “poles of the life-cell which belong inseparably together, into which from outside the spirit, like a wedge, inserts itself, in the endeavour to split them apart, to ‘de-soul’ the body, to disembody the soul, and in this way finally to kill all the life it can reach’”. [13]

And he adds that the resulting “unconscious ill will, called narrow-mindedness, can just as little be broken or won round as one could transform the blood of its carrier”. [14]

The element that Klages opposes to his “spirit” is “soul”, which represents everything that this stifling “spirit” denies.

This is not merely a pole of human living, but also manifests in the form of “the elementary souls” [15] he says, invoking “the souls of the images of light and darkness, warmth and cold, storm and calm, of cliff and tree, river and sea, wood and desert, of sunlight and moonlight, starry sky and daylit heaven, gorge and peak”. [16]

From a Winter Oak perspective, it is good to see our totem tree get a special mention.

Writes Klages: “If, in an inspiring moment, the ‘psychic’ individual is able, instead of perceiving the oak-tree (whether with, or without, ‘aesthetics’), to envision its ‘primordial image’, then, by means of the same object which for us means a tree with such-and-such qualities, a daimonic soul has appeared to him, and this means: he has sensed as overpoweringly real the fluid shudder which mysteriously whispers down from the tree-top”. [17]

Sometimes he imagines these souls as gods: “There are gods of water and gods even of particular stretches of water, gods of the plant kingdom as well as of a particular tree, gods of the hearth as well as of the hearth of a particular house, but also gods of the night, of the day, of the dawn, of the light, of the darkness, of the thunderstorm, of the rainstorm, of lightning, furthermore of love, friendship, revenge, reconciliation, of anger, furthermore of death, of sickness, of fertility, finally of prayer, sacrifice, exchange, healing, making war, swearing, warding off evil and so on into infinity”. [18]

Klages sees this depiction of elemental essences in a famous painting by Arnold Böcklin, Playing in the Waves (Im Spiel der Wellen), in which the mythological figures represent “the soul of water”. [19]

He explains: “The huge, ungainly water centaur, the mermaid in the foreground, the lascivious merman next to her, the person plunging to the depths of the sea behind her, are not least essentially one and the same as the water from which they emerge”. [20]

He also describes these gods as “the ancestral souls” and says that “the souls of the past that appear” are the “primordial images” (Urbilder). [21]

This notion of Urbilder – that is to say, archetypes – is central to Klages’s thought.

In one context they are the guiding image within life that causes it to take the shape it was meant to take.

He writes: “We could hardly better describe the growth process than with the observation that, in the fertilized cell, the image of the developing body works as a material-shaping power!” [22]

He discusses the nature of this image in the way in which a nut or acorn falls from one tree and grows into a new one.

“If, however, in the new individual neither the old individual nor its matter remains, what is it actually that uninterruptedly persists through thousands and thousands of generations?

“The answer is an image. The image of the oak, the image of the pine-tree, the image of the fish, the image of the dog, the image of the human being recurs in every single individual carrier of the species.

“‘Reproduction’ means the physically eternally inaccessible process of the handing-on of the primordial image of the species from place to place and from time to time”. [23]

In another context Klages suggests that the ancient power of these images, these Urbilder, makes itself apparent in conscious reality through poetry and artistic creation . [24]

The idea of these Urbilder, or archetypes, should not be regarded as suggesting a static, fixed, reality, as everything in the natural world is always moving and renewing.

The rhythms of reproduction, of life and death, of the stars and planets, of the ocean’s waves and of human hearts are, for Klages, the pulse of one great living.

But this cosmic rhythm is never restricted to the rigid repetition of a beat, stresses Klages.

“Steam engines, drop-hammers, pendulum clocks function to a beat, but not in a rhythm; a piece of perfect prose has a perfect rhythm, but certainly not a beat.

“Life expresses and manifests itself in rhythms; by contrast in a beat the spirit compels the rhythmic life-pulse to submit to its own peculiar law”. [25]

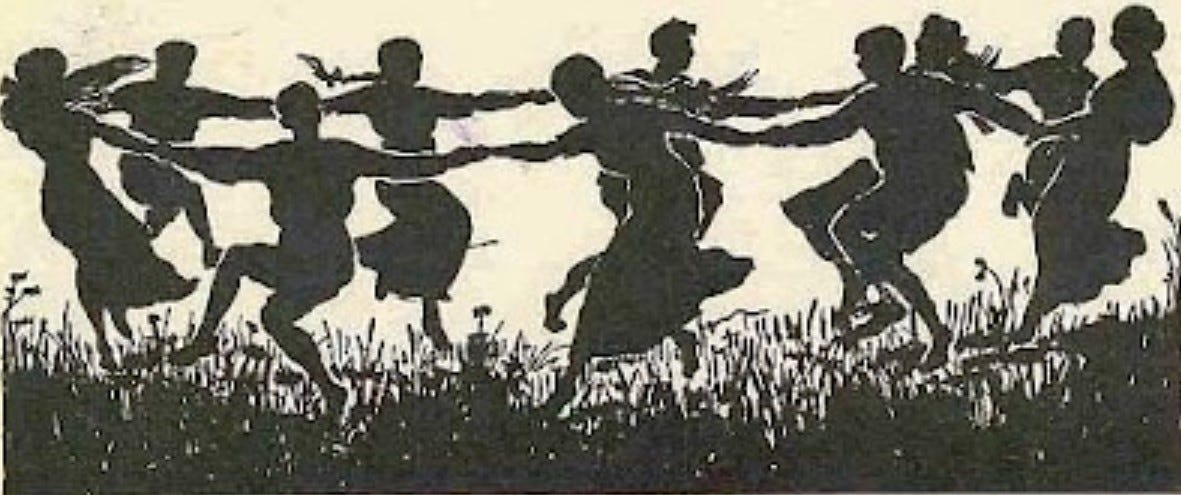

We can access a different dimension of existence by allowing ourselves to follow that life rhythm, says Klages – for example, when, in dancing, we lose ourselves and become part of the pulsating universe.

“The more the dancer is granted the grace of becoming completely absorbed in the dance, the more it is not about movements, not about a change of locations and a measuring of line segments, but about the will-less, indeed almost impulse-less, resonance in the element of a wave-creating motion, which henceforth experiences and, while it is experiencing, at the same time is ‘worked and woven’.

“In the rhythmically perfect dance something reaches its consummation as a primordial unique experience which, in the meantime, is experienced only at the sight of falling leaves, passing clouds or the surge of ocean waves: the sense of being carried away by the stream of things in action”. [26]

It is here that we might touch ecstasy or Rausch, which Klages defines as “to be outside oneself’ (= outside the ego)”. [27]

Lebovic explains: “For late romantics, Rausch swept away all thought of boundaries, even the idea that one might transgress boundaries through a conscious decision.

“According to Nietzsche, there was nothing conscious, so no choice, about transgression; rather, the forces of existence itself led back into the primordial, the animalistic roots, a prehistoric source, before the birth of modern civilization”. [28]

With Rausch we reach an entirely unmediated primal state of being, normally only accessible to us modern humans when we sleep and dream.

We can hope to taste what Klages hailed as “the magical rotating of a primordial time in which soul and world fused with each other in rhythmically uninterrupted, mutually consecutive embraces”. [29]

Klages regards poetry as another means by which we can reach beyond the narrow restraints of our modern being.

He writes: “Although the poet remains an individual, he still remains an aspect of the cosmic flux: he is animal, star, sea, plant; he is the eye of the elements; he is matriarchal and earthly to the core. The praxis by which he expresses his inner vision is magic“. [30]

“Let there be no mistake: either the most powerful poetry and art of all times is sheer invention – no, a smoke screen – or it is a magic means of opening up to us real worlds, to which we would on our own no longer find a way, out of our dungeon of believing in facts”. [31]

“The praxis of our philosophy is magic, it itself is the theory of magic… It works with images and symbols, and its method is the method of analogy. – The most important names for it are: element, substance, principle, daimon, cosmos, microcosm, macrocosm, essence, image, primordial image, vortex, tangle, fire – Its ultimate formulas are magic spells and have magical power”. [32]

At the same time as re-enchanting our world, Klages says his life philosophy aims to “renaturalize the human person”. [33]

But then this is probably one and the same process, given Klages’s belief in the souls of nature.

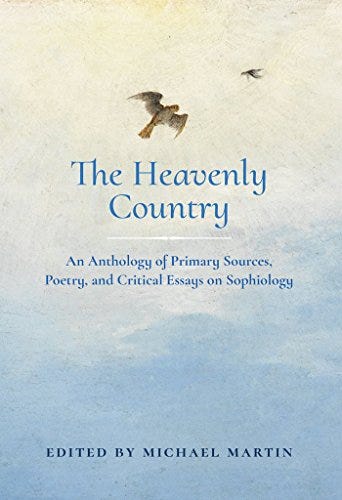

Despite Klages’s differences with Christian thought, I can’t help seeing important similarities with the sophiological outlook I presented in a recent essay series. [34]

Is there fundamentally any conflict between Klages’s pagan notion of the “divinity of life” [35] and Jennifer Newsome Martin’s “bright and hidden flame of divine presence that permeates the natural world and the human beings within it”? [36]

And is his “knowledge that there is a love which encompasses the whole world in its creative weft” [37] really something different from Martin’s gnosis that she says allows us to see by intuition “the glorious invisible that suffuses and illuminates the world”? [38]

As we will see in the third and final essay, Klages certainly joins Michael Martin, editor of The Heavenly Country, in his opposition to “an age of the totalization of the technological and the technocratic, an age of the unreal, the artificial, the illusory, of the simulacra”. [39]

Can we not open up a spiritual dimension to the beyond-left-and-right transcendence of Klages’s political thinking?

Is it not time for all of us who cherish divine nature and true living – whatever our philosophical or religious backgrounds – to come together to defeat the vile industrial-financial Beast and to restore love, soul and magic to this essentially beautiful world?

See also:

Life philosophy: beyond left and right

[1] “He will essentially follow the language of the spectacle, for it is the only one he is familiar with; the one in which he learned to speak. No doubt he would like to be regarded as an enemy of its rhetoric; but he will use its syntax. This is one of the most important aspects of spectacular domination’s success”. Guy Debord, Commentaires sur la société du spectacle (Paris: Gallimard, 1992), p. 38.

https://orgrad.wordpress.com/a-z-of-thinkers/guy-debord/

[2] Ludwig Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, 6th edition (Bonn: Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann, 1972), p. 1132, Paul Bishop, Ludwig Klages and the Philosophy of Life: A Vitalist Toolkit (Abingdon/New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 81.

[3] Ludwig Klages, L’Homme et la terre (Mensch und Erde), trad. Christophe Lucchese (RN Editions, 2016), p. 40. Quotations from this book are my own translations from French.

[4] Bishop, p. 101.

[5] Gilbert Merlio, ‘Préface’, Klages, L’Homme et la terre, p. 10.

[6] Nitzan Lebovic, The Philosophy of Life and Death: Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p. 201.

[7] Paul Cudenec, ‘Volk and freedom’, Against the Dark Enslaving Empire! (Winter Oak, 2024), pp. 155-70, https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/against-the-dark-enslaving-empire-online.pdf

[8] Bishop, p. 91.

[9] Ludwig Klages, Vom Wesen des Bewusstseins, Sämtliche Werke 3, ed. Ernst Frauchiger, Gerhard Funke, Karl J. Groffmann, Robert Heiss and Hans Eggert Schröder, 9 vols (Bonn: Bouvier, 1964-1992), pp. 391-92, Bishop, p. 135.

[10] Bishop, p. 139.

[11] Lebovic, p. 131.

[12] Ludwig Klages, Ausdrucksbewegung und Gestaltungskraft, Sämtliche Werke 6, p. 257, Bishop, p. 139.

[13] Ludwig Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, 6th edition (Bonn: Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann, 1972), p. 7, Bishop, p. xxi.

[14] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, pp. 799-800, Bishop, p. 87.

[15] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 1138, Bishop, p. 101.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ludwig Klages, Von kosmogonischen Eros, Sämtliche Werke 3, p. 293, Bishop, p. 148.

[18] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 202, Bishop, p. 102.

[19] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, pp. 1127-31, Bishop, p. 83.

[20] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, pp. 1127-31, Bishop, p. 84.

[21] Klages, Von kosmogonischen Eros, p. 452 & p. 470, Bishop, p. 102.

[22] Ludwig Klages, Die Grundlagen der Charakterkunde, Sämtliche Werke 4, pp. 322-25, Bishop, p. 75.

[23] Ludwig Klages, Handschrift und Charakter, Sämtliche Werke 7, p. 332, Bishop, p. 86.

[24] Ludwig Klages, Vom Traumbewusstsein, Ein fragment (Hamburg: Paul Hartung, 1952), p. 10, Lebovic, p. 155.

[25] Ludwig Klages,Grundlegung der Wissenschaft vom Ausdruck, Sämtliche Werke 6, pp. 626-28, Bishop, p. 128.

[26] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 1054, Bishop, p. 131.

[27] Ludwig Klages, Vom Wesen des Bewusstseins, Sämtliche Werke 3, pp. 391-92, Bishop, p. 135.

[28] Lebovic, p. 111.

[29] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 1190, Bishop, p. 168.

[30] Ludwig Klages, Rhythmen und Runen, Nachlass herausgegeben von ihm selbst (Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1944), p. 261, Bishop, p. 103.

[31] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 1185, p. 167.

[32] Klages, Rhythmen und Runen, p. 312, Bishop, pp. 167-68.

[33] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 1308, Bishop, p. 170.

[34] Paul Cudenec, ‘The Spirit of Sophia‘.

[35] Klages, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, p. 1424, Bishop, p. 185.

[36] Jennifer Newsome Martin, ‘True and Truer Gnosis’, in The Heavenly Country: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Poetry, and Critical Essays on Sophiology, edited by Michael Martin (Kettering, Ohio: Angelico Press/Sophia Perennis, 2016), p. 346.

[37] Klages, L’Homme et la terre, p. 60.

[38] Newsome Martin, ‘True and Truer Gnosis: The Revelation of the Sophianic in Hans Urs von Balthasar’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 346.

[39] Michael Martin, ‘Introduction: Sophiology: Genealogy and Phenomenon’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 1.

Source: https://paulcudenec.substack.com/p/life-philosophy-soul-rhythm-magic

Article courtesy of Paul Cudenac. https://paulcudenec.substack.com/