The nature writer Richard Jefferies, a great inspiration for me, explained once why he always went for the same country walk and did not go elsewhere for a change.

He wrote: “I do not want change; I want the same old and loved things, the same wild flowers, the same trees and soft ash-green; the turtle-doves, the blackbirds, the coloured yellow-hammer, sing, sing, singing so long as there is light to cast a shadow on the dial, for such is the measure of his song, and I want them in the same place”. [1]

His words resonate strongly with me. I, too, do the same walks time and time again without ever growing tired of them.

I also generally feel there is a great benefit to be had from viewing life from a fixed spot.

For one thing, intimate long-term knowledge of the land allows you to feel its cycles, providing a rooted rhythm for your own living.

It also allows you to see the changes that take place over the years, in a way that you obviously cannot do if you flit around all over the place.

It was, for instance, my quarter of a century in West Sussex that allowed me to understand the sheer evil of the money-driven “development” phenomenon that has destroyed so much of the once-beautiful English countryside.

I watched nature being gobbled up by the Greed Machine – field by field, copse by copse – at a frantic speed imposed by the system’s cold-hearted planners.

“Mobility” is one of the main qualities required for participation in the modern world and a certain gnawing restlessness is typical of our age.

People today grow tired of where they live, imagine their inner life would be improved by different external surrounds, are for ever seeking novelty and superficial stimulation.

They are generally happy to adapt to the social and practical changes brought about by Technik and seem to accept not only the relentless advance of this life-altering process but also its perpetual acceleration, which has likewise been presented to them as not only desirable but inevitable.

The need for “change” is part of the manufactured Zeitgeist and is bandied around by politicians trying to win elections as if it were necessarily a Good Thing.

But, strangely enough, the “systemic change” agenda [2] leading us towards totalitarianism and transhumanism is also supported by a fear of change.

The change of which many people are afraid is a change away from the path of ongoing industrial development to which they have become accustomed and addicted.

They have internalised criminocratic propaganda to such a degree that they really believe this is the best possible future for humankind.

Therefore they are very suspicious of, even hostile to, anyone who dares suggest that we need to take a different civilisational direction.

Confused by the use of apparently “green” rhetoric by the system itself, some can even conclude that anyone proposing de-industrialisation is part of the technocratic plot to enslave us all.

In fact, de-industrialisation is the last thing the criminocracy would support, since its entire project is built on expanding Technik as a means of both extracting profit and exerting control – so that further profit can be extracted!

I do understand why anyone who has always lived with washing machines and fridges and vacuum cleaners and airports and motorways might be alarmed by the prospect of all that going away.

But I don’t see how anyone can seriously argue that any of that is actually necessary for us to lead pleasant lives.

After all, our ancestors lived for hundreds of thousands of years without the “conveniences” of the industrial world and managed perfectly well to raise children who produced more children, on and on for countless generations.

It seems to me to be sadly ironic that in an age when everyone calls for constant change, the one change that most are afraid of is the only change that would be in the right direction!

The future being pushed by the criminocrats is the really frightening one, with its vaunted aim of abolishing the human being as we know it.

That future not only represents the unknown, but a change we surely do not want to ever know.

However, there is nothing scary about the prospect of turning our backs on global centralisation, on the military-industrial complex, on data-harvesting and surveillance, on Big Pharma and the World Bank, on lithium mines and nuclear power stations.

There is nothing scary about scaling down our societies, growing our own food, educating our own children, creating our own cultures, defining our own needs, nurturing our own values, living to the deep and slow rhythms of the Earth that bore us.

Embracing the world offered by this kind of change – decentralising, de-industrialising, re-localising, re-humanising change – does not even involve facing the unknown.

We all already know that world – deep in our hearts, deep in our dreams, deep in our collective memory.

It’s our home and we want to go back there.

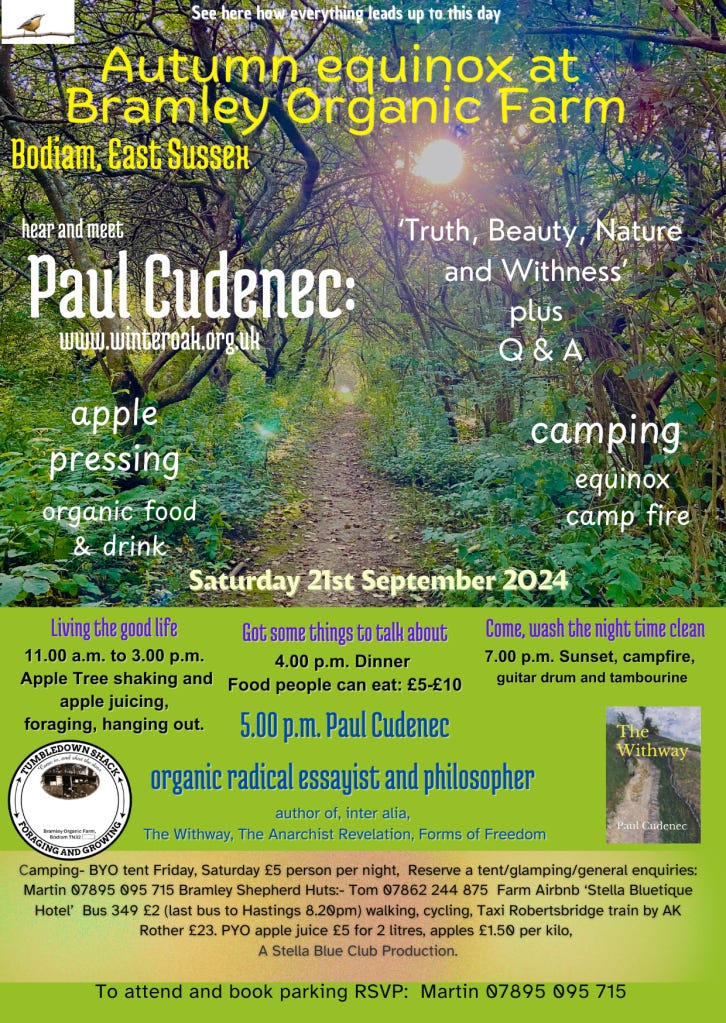

I’m going to be giving a talk in East Sussex, England, on Saturday September 21, 2024. Here is the flyer with all the details.

[1] Richard Jefferies, The Open Air, cit. Henry Salt, Richard Jefferies: His Life and His Ideals (Sussex: Winter Oak Press, 2014), pp. 118-19.

[2] The most sinister use of the word “change” comes perhaps in the title of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change.

Source: https://paulcudenec.substack.com/p/change-for-the-better

Article courtesy of Paul Cudenac. https://paulcudenec.substack.com/