People across the world being “locked down” in digital prisons during the Covid period was not a one-off event but “the culmination of tendencies which have been at work for a long time”, [1] says French author Aurélien Berlan.

The message of Terre et liberté: la quête d’autonomie contre le fantasme de délivrance (‘Land and freedom: the quest for autonomy against the fantasy of deliverance’) is that we have been dispossessed and disempowered – systematically reduced to total dependency on an industrial system that does not wish us well.

When one also considers the war on small farmers being conducted under the same Great Reset banner, and the sinister “managed retreat” project to clear people out of the countryside and into smart cities, [2] his warning rings even more true.

Berlan writes: “In the 20th century, the working classes of industrialised nations became dependent, for their subsistence, on a system over which they had no control, contrary to the ruling classes.

“And as the latter also controlled the state, they had their hands on the power to police and to feed.

“We can understand the feeling of powerlessness that has become so widespread today. Consumer society is based on the delegation of our material existence and we have become its hostages”. [3]

Because modern lives depend on industrial infrastructure like the electricity grid and transport networks, we are in thrall to the “big state and industrial organisations that operate them”, [4] he says.

Our loss of autonomy is reflected in the standardisation of life and culture: “The more we live somewhere in the same way as everywhere else (when we eat the same world food, when we follow the same fashions, etc), the more our way of life is heteronomous, dependent on the global market”. [5]

“Industrial development led to radical transformations in the means by which culture was spread. The emergence of mass media gradually penetrated to the heart of society, even into the private realm…

“This allowed state and Capital to invite themselves into each and every household and turn family intimacy into mere proximity: the life of the family was no longer centred on itself, but turned towards the consumption of ‘cultural content’ produced elsewhere in an industrial manner.

“Mass media were, basically, the Trojan Horse through which the private sphere was invaded by social forces advancing cultural standardisation”. [6]

This globalising standardisation is closely linked to the drive for “economies of scale” – “as production increases, our activities are organised on a scale beyond the scope of our control and representation, being shaped by social macrostructures and destructive technology”. [7]

“While knowing that this is leading to disaster, we cannot see how to get out of it: we are its prisoners, materially and mentally, individually and collectively“. [8]

The general assumption that there is no other way than growth and expansion, more and more quantity and profit, is a key element in our mental imprisonment.

Writes Berlan: “In the supposed ‘energy transition’ that the industrial states boast about pushing, it is never a question of reducing the consumption of energy, but only of modifying the place of a certain source of energy in the overall energy production, which, like GDP, is regarded as having to grow”. [9]

Providing this energy has always required, he says, some form of slavery, whether the millions of miners working themselves into an early grave to dig up coal, or the contemporary extraction, in equally terrible conditions, of the rare metals needed for the production of “clean” energy. [10]

Individuals, says Berlan, are also trapped inside “the vast industrial machine of Capital” [11] by the requirement to have money: “the means of satisfying all needs, it thus becomes that of which we are all always in need”. [12]

In order to obtain money, we work for wages, signing a contract of employment which, in fact, amounts to a “contract of subordination”. He writes: “Employees are required to follow the directives of their employer during paid hours. This is why paid employment was long considered a new form of slavery”. [13]

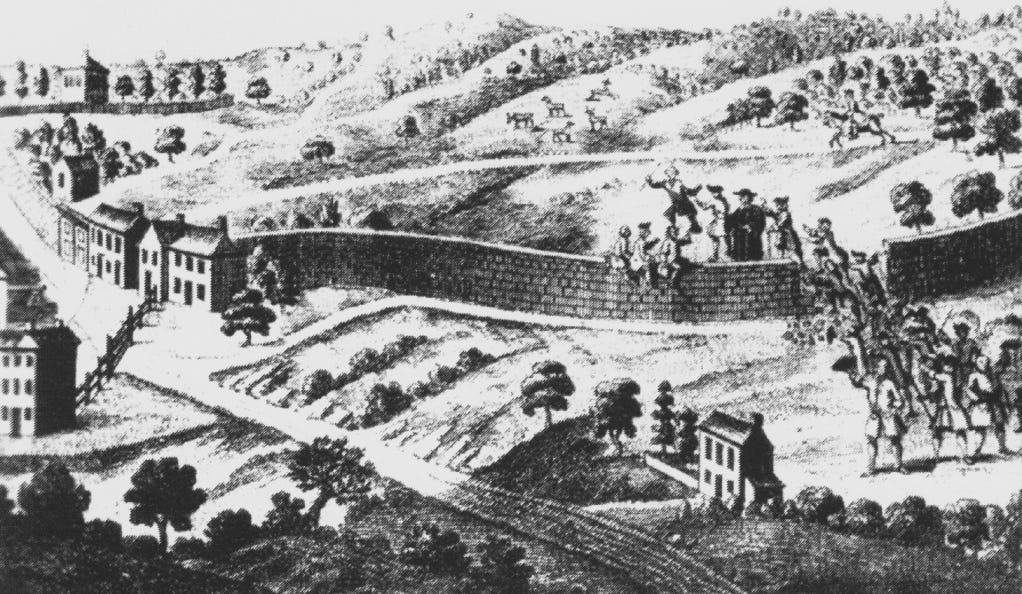

Berlan underlines this connection by referring to the history of black slaves emancipated in the USA. An initiative in 1865 to give each freed family 40 acres and a mule, so they could be self-sufficient, was overturned.

“The slaves had to sell their labour to their previous masters, who were given back the redistributed land. The formally-freed blacks had no other choice beyond enduring another century of exploitation and racial segregation in the South, or migrating to the North, where industrialists were waiting with open arms to exploit them in their factories”. [14]

He observes, on a general level, that “to be able to exist and choose our lives in complete freedom; we must have the means to live and have control over the conditions of our lives”. [15]

Otherwise, he says, we will be “at the mercy of the system and of those who run it”. [16]

Berlan points out that our lives are today totally shaped by a structure that has made itself indispensable in many different ways.

The most important of these is our food supply, of course. Not many regions, let alone families or individuals, can claim to be self-sufficient in this respect.

But the problem is even wider. The author points out, for example, that while it is easy enough to say that having a motor vehicle is not a real “need”, those living outside big towns and cities can find their everyday activities difficult without one – because they are living in world that has been designed and built around the use of that means of transport. [17]

So how did we get here? How did those who run the system manage to successfully reduce us to a state of dependence, and thus enslavement, to their machine?

Berlan describes several intertwining strands in this process, ranging from the philosophical to the physical, and it seems clear to me that they add up to one overall act of deliberate dispossession.

The main narrative that has steered us down the path of industrial slavery is that it in fact amounts to liberation, explains the author.

Its “progress” has supposedly freed us from the need to do all that tiresome work of growing our own food, fetching and chopping wood or washing our clothes by hand.

The modern person feels that their life is easier, more comfortable and more advanced – thanks to all the infrastructure surrounding them, they can fulfil their own individual potential in other ways, goes the story.

The industrial system is thus everywhere “accepted and perceived as favourable to freedom”. [18]

But, as we saw to such a shocking extent with the Covid totalitarianism and the ongoing threat of smart-city digital slavery, this is the inversion of the truth: our freedom is anathema to the system.

While assuring us it is liberating us, the industrial machine is actually imposing what Berlan calls “the domination of industrial organisations and the oligarchies that run them”. [19]

Not seeing this fundamental contradiction between narrative and reality requires a real leap of faith.

“Belief in Progress by means of techno-science has performed the same function, in the modern era, as religions: convincing the exploited to be patient by saturating them with illusory promises of the ‘radiant future’ that lies before them”. [20]

Berlan traces back the idea of being “freed” from everyday subsistence tasks to the desire of ruling groups, throughout history, to achieve just this.

Their way of doing so was, of course, to get other people to do the work for them, while they got on with their “superior” activities.

How? The most obvious means, which has always lurked behind the justifying rhetoric, is physical compulsion of one kind or another.

If you deprive people of their means of self-sufficiency, such as by enclosing the common land which had always been available to them and their ancestors, they are forced to seek survival in another way.

The deliberate nature of this historical dispossession is beyond doubt and Berlan turns to industrial-imperialist Britain for confirmation of the agenda.

“The central question for the modern dominant classes was to know how to push the poor into work, how to put them at their service.

“In England and elsewhere they passed brutal laws so as to force them, under threat of death or imprisonment in public workhouses, to take on paid work”. [21]

Berlan refers to a proposal for the reform of the Poor Law presented to the British government in 1697 by the liberal John Locke in which he outlined how to achieve “the setting of the poor on work”. [22]

Here Locke declared that people reduced to begging in order to eat – “idle vagabonds” – should be arrested, sentenced to hard labour or forcibly conscripted into the navy.

Locke pointed to the profitable potential (a million pounds in eight years, he calculated) of forcing 100,000 English peasants into “labour in the woollen or other manufacture”.

He added: “The children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour is also generally lost to the public till they are twelve or fourteen year old”.

To cash in on the human capital of children between three and fourteen years old, Locke proposed enslaving them in “working schools”, again involving “woollen manufacture”.

He enthused: “The children will be kept in much better order, be better provided for, and from infancy be inured to work, which is of no small consequence to the making of them sober and industrious all their lives after”.

Locke identified the added bonus that their mothers would thereby also be “liberated” to work for the nascent industrial system.

A century later, in 1786, Joseph Townsend was keen to starve the English serfs into participation in industrial society.

He wrote: “Hunger will tame the fiercest animals, it will teach decency and civility, obedience and subjection, to the most brutish, the most obstinate, and the most perverse”. [23]

In France, in 1825, liberal Charles Dunoyer addressed the problem of finding potential workers for the new factories, suggesting that those targeted, “no longer having the basis on which to look after themselves and procure the means of living, will be obliged to hire out their services”. [24]

And, back in Britain, in 1835, Andrew Ure gloated in his pro-industrialist book The Philosophy of Manufactures: “When capital enlists science; in her service, the refractory hand of labour will always be taught docility”. [25]

The same authoritarian fervour had been in evidence when the Luddite revolt between 1811 and 1817 led the panicking British Crown to introduce the death sentence for machine-breaking, notes Berlan. [26]

With all this in mind, it is ironic, not to say tragic, that the ruling-class enthusiasm for industrialism has been so enthusiastically shared by their supposed enemies on the “left”.

This was not always the case, Berlan notes. Before the industrial revolution, popular movements were not calling for the labouring classes to be relieved of the need for physical effort.

Instead, their complaints revolved around the oppression and over-work inflicted on them by those in power who considered such tasks beneath them, he says.

“To this end, they demanded free access to the means of subsistence allowing them to meet their needs”. [27]

He illustrates this with reference to the “12 articles” put forward by German peasant insurrectionaries in 1525, which focused on the abolition of certain forms of domination and certain taxes, and demanded the freedom to hunt and fish, along with the restoration of common land.

Berlan concludes: “Emancipation, for the working classes, was thus not about being freed from tasks linked to everyday life, but about abolishing relationships of domination”. [28]

Even in the 19th century, French peasants were resisting the methods being deliberately deployed to force them into industrial thraldom.

In the Ariège region, the long-running “Demoiselles” revolt declared war “against the state which was depriving them, with new forestry laws, of their ancient usage rights such as gathering wood or grazing animals – which amounted to preventing them from living by their own means, on the basis of local resources”. [29]

The contemporary left’s love of industrialism seems to have been based on the mistaken belief that, in using machines to exploit the forces of nature, industrialism was not exploiting human beings.

Berlan writes: “The domination of nature opens up the fantastical possibility of a complete and universal deliverance, compatible with the ideal of liberty and equality for every individual”. [30]

He says left-wingers “share the same ‘industrial religion’ as liberals: faith in economic and techno-scientific development.

“For Marxists, emancipation is identified with industrial progress: and the left as a whole takes it as read that it was steam power that liberated the blacks and the washing machine that emancipated women”. [31]

“This led to them theoretically separating capitalism (reduced to private property, source of the oppression) from industry (mass production, which they saw as emancipatory), even though, for two and a half centuries, capitalism’s expansion has in practice been identified with the industrialisation of production”. [32]

The left has always been fully on board the post-WW2 bandwagon of “development” says Berlan, describing this as “the official ideology of the West”, the “new name for Progress”. [33]

Strangely, many leftists fail to see that it is also the new name for imperialism!

Peoples on the receiving end are certainly well aware of this. Berlan quotes one indigenous activist in Colombia as declaring in 2016: “We are fighting to not have roads and electricity – this form of self-destruction that is called ‘development’ is precisely what we want to avoid”. [34]

Indeed, he says, development everywhere really amounts to “internal colonisation”, [35] with the external occupying force being that of rapacious global Capital.

I would not want to give the impression that Terre et liberté focuses exclusively on the oppression of the industrial system and the failure of the left to challenge it.

Berlan writes that his book is “an invitation to dream otherwise” [36] and underpinning his critique of contemporary modernity is a vision for a non-industrial future.

Like Jean-Pierre Tertrais, whose book I recently reviewed, he cites several organic radical inspirations – William Morris, George Orwell, Gustav Landauer, Gerrard Winstanley and Mohandas Gandhi.

This desire for a different way of existing has already been physically expressed in France with the ZADs (‘Zones to Defend’) that have sprung up in opposition to various industrial projects.

Berlan says this movement “bears witness to a desire to win back the freedom of which we have been dispossessed by the capitalist system with unfailing state support”. [37]

This is the freedom to feed ourselves without lining the pockets of the agro-industrial cartels; to live in cabins that don’t conform to planning norms or to cure ourselves with frowned-upon natural remedies.

It is “a freedom intimately connected to the land, following on from all those political movements of the 19th or 20th centuries who, from Mexican revolutionaries to Russian ‘populists’, via the Spanish anarchists, took as their rallying cry ‘Land and Freedom!’”. [38]

The aim is autonomy: to be independent, as a community, of any outside system, of the money through which it exercises its control and thus of the need to perform paid labour for that system so as to simply be able to stay alive.

One of the features of this other – and always possible – world would be the disappearance of “work” in the sense of the current wage slavery.

What would “work” mean, anyway, when we had removed the element of compulsion that makes it so objectionable?

Berlan remarks: “For a professional musician, music would be work and digging the soil leisure, while for a farmer the opposite would be the case”. [39]

Localisation is also important, a scaling-down of production and social organisation to a level at which “direct democracy can make sense”. [40]

Berlan identifies an alternative to old “capitalist” and “communist” models in the idea of traditional local markets regulated by what he calls a “moral economy”. [41]

He finds inspiration in Alexandre Chayanov’s descriptions of the domestic economy of traditional Russian peasantry, which was based on a balance, varying from family to family, between “the degree of satisfaction of needs and the degree of hardness of work”. [42]

To get out of the current industrial-totalitarian bind, we therefore need to “rethink our needs, rediscover know-how that technology has caused us to lose, learn again to live locally”. [43]

The trouble is, of course, as Berlan points out, [44] that the industrial system doesn’t want us to escape its grip.

It did not spend centuries purposefully dispossessing us of our autonomy and self-sufficiency simply to let us slip away back into the fields and woods that our ancestors knew.

Anyone calling for genuine freedom, for autonomy, for the relocalisation of both production and decision-making, can only ever be seen as an “enemy”. [45]

The system regards us as its property, its slaves, and will use all the considerable means at its disposal to keep us in chains.

On the physical level, Berlan says anyone trying to break free will necessarily find themselves “in open conflict with industrial society and its governance”. [46]

He warns: “Subsistence cannot make us free if we are not able to take care of our own defence”. [47]

On a pro-active note, he adds: “The secession involved in no longer feeding the mega-machine is not enough: we also have to sabotage it”. [48]

Some ideological self-defence, and counter-attack, is likewise badly needed.

As well as using the myth of a “liberating” progress to advance its agenda, the system has also long deployed it to condemn any “backward-looking”, “reactionary” or “utopian” calls for an exit from industrialism. [49]

Subsistence living – balancing our needs and means in harmony with our own desires and with nature – is presented as an undesirable condition.

It is associated with poverty – painted as amounting to not having enough to live on, rather than simply having enough. [50]

The idea of reducing our needs has been declared impossible by our industrialist rulers, because it “contradicts their idol – development”, [51] says Berlan, and history has been rewritten to suit the narrative.

“It’s the science dedicated to this idol, the economy, that created the notion of a subsistence economy so as to contrast it to the market economy, supposedly the source of ‘abundance’.

“As development presupposes the commodification of resources – thus their appropriation by a minority who get rich while the majority, dispossessed of their means of living, sink into misery – the idea had to be established that the entire past was afflicted with scarcity”. [52]

Anti-industrial ideas have been consigned to oblivion by “dominant thinking, even supposedly radical” [53] with, for instance, prominent social critic Michel Foucault disqualifying (in 1979) all criticism of consumer society as akin to Nazism! [54]

Meanwhile, recuperation of environmental language by pro-system authoritarians has served to further discredit the anti-industrial outlook in the minds of many.

Berlan comments: “If we want to stop worsening the socio-ecological disaster, it is not freedom that has to be restricted, as suggested by so many intellectuals and ‘personalities’ with all their calls for an environmental state of emergency, or even an environmental dictatorship.

“Giving unlimited power to the pyromaniacs in power will never transform them into firefighters”. [55]

I should mention that Berlan was recently one of several targets for a ridiculous smear attack in an anonymous booklet published on various left-wing French websites, which I have previously dissected. [56]

It basically depicts the anti-industrial movement in France as “reactionary” and tainted with connections to various “right-wingers”, as well to as a notoriously “anti-semitic” English dissident whose words you are currently reading!

Does anyone seriously think that there is no link between the left’s historical complicity with industrialism, its general enthusiasm for the globalist “sustainable development” scam and its smear attacks directed against the anti-industrialist movement?

To what extent one can even separate the industrial-financial agenda from that of the historical “left” is a moot point, as I explained in The False Red Flag.

But it seems quite clear to me that the apparent angle of attack – a virtue-signalling “radical” leftist one – is fake and that the real perspective of the booklet is that of the industrial system itself, seeking to discredit people it regards as a threat.

We have to realise, when we look at the techno-authoritarian world we live in today, that it did not come into being by chance.

Each step our society has taken on the road to this industrial prison has been taken on purpose, to drag us in that direction.

As Berlan shows, our ancestors were deliberately dispossessed of their means of living so as to force them into industrial servitude.

The myth of technological liberation, of the easier, happier life provided by so-called Progress, has been deliberately drummed into us until it seems to most to be self-evidently true.

Likewise, the dismissal of calls for autonomy, the stigmatisation of anti-industrial thinking, has been deliberately orchestrated to protect the industrialist programme.

And if all this has been done deliberately, this means that some entity has been behind it.

Berlan points to the existence of this entity on several occasions, writing about “the industrial supermarket of the globalised economy”, [57] submission to “the global market (that’s to say to the industrial powers that dominate it)” [58] and “big private and public organisations and the industrial system that they constitute”. [59]

He correctly states that modern capitalism and colonialism are one and the same thing [60] and that we are living in a world system “that the powerful have constructed in their own interests”. [61]

It is important, in my view, to be able to combine a theoretical understanding of historical processes with an awareness of the very real physical groups pulling the strings behind the scenes.

Both realms of insight are crucial and their coherent combination essential.

It is not enough to have identified the dangers of the Great Reset, the “sustainable development” and Fourth Industrial Revolution agenda currently being imposed on us by the WEF-UN-Rothschild mafia, without grasping that this is the culmination of a centuries-long process of globalist imperialism and that the First, Second and Third Industrial Revolutions were the stepping stones that got us where we are today.

Equally, it is not enough to have completely understood the historical background, but to shy away from making the link to specific current-day threats or plans for fear of being labelled a “conspiracy theorist”, or to avoid mentioning particular industrial-financial individuals or networks lest this identify you as a so-called “anti-semite”.

We need to build a broad dissident outlook that takes a holistic approach, combining historical with contemporary insights; detail with overview; a critique of the methods and lies of the criminocrats’ dark enslaving empire with a solid and powerful alternative worldview of its own.

It is only by properly describing – to ourselves and to the outside world – the identity and methods of the enemy who has dispossessed us and, alongside this, our own vision of a free future, that we can we hope to conjure into being a resistance movement to replace the failed 19th and 20th century models that helped lead us into this dreadful trap.

[1] Aurélien Berlan, Terre et liberté: la quête d’autonomie contre le fantasme de délivrance (St-Michel-de-Vax: Editions La Lenteur, 2021), pp. 140-41. Subsequent page references are to that work.

[2] ‘Exposed: how the climate racketeers aim to force us into smart gulags’, https://winteroak.org.uk/2024/06/25/the-acorn-94/

[3] p. 127.

[4] p. 126.

[5] pp. 193-94.

[6] pp. 43-44.

[7] p. 155.

[8] p. 10.

[9] p. 120.

[10] p. 121.

[11] p. 20.

[12] p. 19.

[13] p. 43.

[14] p. 159.

[15] p. 166.

[16] p. 166.

[17] p. 180.

[18] p. 53.

[19] p. 104.

[20] p. 81.

[21] p. 91.

[22] https://oll-resources.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/oll3/store/titles/2331/Locke_PoorLawReform1697.pdf

[23] http://pombo.free.fr/townsend1786p.pdf

[24] Charles Dunoyer, L’industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (Paris: Sautelet, 1825), p. 373, cit. p. 116.

[25] https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044010389476&seq=392&q1=science

[26] p. 107.

[27] p. 144.

[28] pp. 144-45.

[29] p. 145.

[30] p. 96.

[31] p. 70.

[32] p. 10.

[33] p. 122.

[34] p. 123.

[35] p. 124.

[36] p. 213.

[37] p. 17.

[38] p. 17.

[39] p. 134.

[40] p. 155.

[41] p. 165.

[42] p. 181.

[43] p. 207.

[44] p. 212.

[45] p. 156.

[46] p. 196.

[47] p. 196.

[48] p. 212.

[49] p. 13.

[50] p. 162.

[51] p. 163.

[52] p. 163.

[53] p. 149.

[54] p. 20.

[55] p. 204.

[56] https://winteroak.org.uk/2023/12/02/targeted-and-smeared-by-the-fake-left-thought-police/

[57] p. 164.

[58] p. 157.

[59] p. 170.

[60] p. 157.

[61] p. 172.

Source: https://paulcudenec.substack.com/p/deliberate-dispossession-and-the

Article courtesy of Paul Cudenac. https://paulcudenec.substack.com/