“This was the Beauty and excellence of Eternal Nature, that all her divided, contrary properties were united into one undivided property in the Eternal Earth, where all their contrarieties were reduced to the most perfect union, agreement and harmony”. [1]

So writes the English mystic John Pordage in his 1683 work Theologia Mystica or The Mystic Divine of the Aeternal Invisibles, an extract of which is included in The Heavenly Country: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Poetry, and Critical Essays on Sophiology, a book which I introduced in my last essay.

He identifies “Natural Goodness” in the way that the archetypal elements around us, his “aeternal invisibles”, complement and harmonise with each other within the Whole.

“All these qualifying powers of Nature have sensibility and mobility in themselves, whereby they can feel and taste one another’s properties”. [2]

This Natural Goodness, the divine wisdom behind the beauty and harmony in the world, is sometimes personified as Sophia, whose tradition is the subject of The Heavenly Country.

One of the contributors, contemporary academic Brent Dean Robbins, looks in detail at the notion of Natura naturans, nature that is never a finished product and always in a state of becoming, referring in particular to the work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

He writes: “Because we become who we are in our essence through our relations with the surrounding world and its beings – and, indeed, because our bodies are formed of and by this encompassing earth – our organs can be understood to be the flesh of the world emerging into consciousness of itself”. [3]

Another academic, Bruce V. Foltz, draws on the fiction of Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky, a friend of Vladimir Solovyov, the “great founder of Russian sophiology” [4] whom I mentioned in the first of these articles.

He says that the spiritual message conveyed in The Brothers Karamazov was one that had hardly been central in the author’s previous novels – “the understanding of nature as a locus for encountering God, nature as deeply expressive of God’s love and wisdom”. [5]

Foltz remarks that this is all the more significant given that Dostoevsky intended the work to serve as “his final testament, the sum of his life-wisdom given to the world”. [6]

He writes: “Nature is everywhere shot through with grace, permeated by what is misleadingly called ‘super-nature’, inherently interwoven with freedom…

“Religious experience intrinsically demands something like Sophia, an infusion of the divine, of this invisible and heavenly, into the visible and earthly”. [7]

Foltz refers to sophiologist Pavel Florensky’s writing about his childhood love of “air, wind, clouds”, where he recalls: “My brothers were cliffs, my spiritual kindred minerals, specially crystals, I loved birds, and most of all growing things and the sea… with all the power of my being. I was in love with nature“. [8]

But, of course, it was not just physical nature inspiring Florensky’s love: “I grew accustomed to seeing the roots of things. That habit of vision later grew through all my thought and defined its basic character – the will to move along verticals and a certain indifference to horizontals”. [9]

Here we touch on the crux of the matter. The notion of Sophia relates not just to nature itself in its physical horizontality, but to its vertical source and becoming, its shape and meaning.

Sophia, and the wild air of her wisdom, is a mythological or religious incarnation of the nurturing relationship between the divine and the living, the metaxu which Foltz defines as “Plato’s term for a connecting link between the visible and the invisible”. [10]

He explains: “It is this numinous draw of creation, perhaps most evident to us in nature – this pull or persuasion or current within the visible that beckons into the invisible – this engaging and evocative interfacing between Creator and creation – that Dostoevsky’s young colleague Solovyov, along with two generations of Russian thinkers; designated by the word ‘Sophia’”. [11]

Russian Orthodox philosopher-priest Sergei Bulgakov writes of the need for a principle that connects God with the world: “The principle we require is not to be sought in the person of God at all, but in his Nature, considered first as his ultimate self-revelation, and second as his revelation in the world… Sophia unites God with the world as the one common principle, the divine ground of creaturely existence”. [12]

He takes care to distinguish his own tradition from that of pantheism, which regards God and nature as being essentially the same. He explains that in the Christian conception “the world belongs to God, for it is in God that it finds the foundation of its reality.

“Nothing can exist outside God, as alien or exterior to him. Nevertheless, the world, having been created from ‘nothing’, in this ‘nothing’ finds its ‘place’. God confers on a principle which originates in himself an existence distinct from his own. This is not pantheism, but panentheism”. [13]

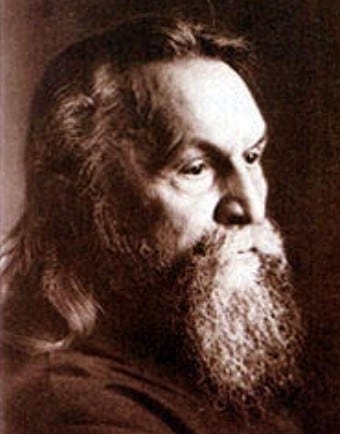

Bulgakov (pictured) adds: “In creating the world by his omnipotence from ‘nothing’ God communicates to it something of the vigor of his own being, and, in the divine Sophia, unites the world with his own divine life”. [14]

It is this fusing of the divine and nature, by the medium of Sophia, that accounts for the beauty of the natural world, from the sophiological perspective.

For Hans Urs von Balthasar, the beauty in this world is nothing less than “spirit as it makes its appearance”, [15] while Solovyov declares that “the absolute actualizes goodness in beauty, through truth”. [16]

Robert F. Slesinksi describes, in The Heavenly Country, Solovyov’s conception of “all-embracing unity at the root of all existence” [17] and of “the absolute goodness, truth, and beauty that is God, constituting, as it were, the all-embracing content or essence of the Divinity”. [18]

He adds: “Reduced to inner unity these three transcendentals – goodness, truth, and beauty – are nothing but forms of love”. [19]

However, people are not always able to appreciate nature in this “vertical” way, with the spiritual feeling that allows us, like Goethe, to experience what Robbins calls “the archetype’s profound beauty”. [20]

We need the gnosis that allows us to see by intuition “the glorious invisible that suffuses and illuminates the world”, [21] writes Jennifer Newsome Martin (pictured).

“To see the world sophianically is to perceive it not as a mechanistic object of experimentation or a medium upon which power can be exercised, but with an awareness of the bright and hidden flame of divine presence that permeates the natural world and the human beings within it”. [22]

Arthur Versluis says that “the Sophianic contemplative process is the awakening of the eye that sees, and the realization of the light-body that participates in eternity, that is, beyond time and space”. [23]

Referring to the work of the English mystic whose thoughts on Eternal Nature began this essay, he explains how Pordage offers “instructions” as to how one can arrive at this inner state, suggesting that it is not so much a question of striving towards it as of allowing one’s consciousness to “sink” into it.

This process of “opening ‘the eye of the heart’” [24] has a significance beyond that of allowing us to enjoy the deep beauty of the natural world.

As I will explain in the last of these essays, it is also the means by which we can find the strength to serve the spirit of Sophia, to channel her wisdom and grace so as to defend nature and its goodness from the dark forces of industrial destruction.

See also: The spirit of Sophia: wild air and wisdom

[1] John Pordage, ‘Theologia Mystica or The Mystic Divine of the Aeternal Invisibles’, in The Heavenly Country: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Poetry, and Critical Essays on Sophiology, edited by Michael Martin (Kettering, Ohio: Angelico Press/Sophia Perennis, 2016), p. 63.

[2] John Pordage, ‘Theologia Mystica’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 62.

[3] Brent Dean Robbins, ‘New Organs of Perception: Goethean Science as a Cultural Therapeutics’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 320.

[4] Bruce V. Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom: How (Not) to Speak of Sophia’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 355.

[5] Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 356.

[6] Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 356.

[7] Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 361.

[8] Pavel Florensky, ‘On the Efimovs’ Puppet Theatre in Paval Florensky, Beyond Vision: Essays on the Perception of Art, ed. Nicolette Misler (London: Reaktion Books, 2002); Pavel Florensky, For My Children, trans. in Avril Pyman, Pavel Florensky: A Quiet Genius (New York: Continuum, 2010), p. 5, cit. Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 365.

[9] Florensky, For My Children, p. 7. cit. Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 365.

[10] Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine’, in The Heavenly Country, pp. 368.

[11] Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 357.

[12] Sergei Bulgakov, ‘Sophia, the Wisdom of God: An Outline of Sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 126.

[13] Bulgakov, ‘Sophia, the Wisdom of God’, in The Heavenly Country, pp. 124-125.

[14] Bulgakov, ‘Sophia, the Wisdom of God’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 125.

[15] Hans Urs von Balthasar, ‘The Glory of the Lord: Volume 1: Seeing the Form’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 137.

[16] Vladimir Solovyov, Sobranie sochinenii, ed. S.M. Solovyov and E.L. Radlov (Sankt-Petersburg, 1911-14), 3:11, cit. Robert F. Slesinski, ‘Russian sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, in THC, p. 330.

[17] Robert F. Slesinksi, ‘Russian Sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 328.

[18] Slesinksi, ‘Russian Sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 329.

[19] Slesinksi, ‘Russian Sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, pp. 329-30.

[20] Robbins, ‘New Organs of Perception’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 323.

[21] Jennifer Newsome Martin, ‘True and Truer Gnosis: The Revelation of the Sophianic in Hans Urs von Balthasar’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 346.

[22] Newsome Martin, ‘True and Truer Gnosis‘, in The Heavenly Country, p. 346.

[23] Arthur Versluis, ‘John Pordage and Sophianic Mysticism’, in The Heavenly Country, pp. 311-12.

[24] Versluis, ‘John Pordage and Sophianic Mysticism’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 311.

Source: https://paulcudenec.substack.com/p/the-spirit-of-sophia-nature-and-grace

Article courtesy of Paul Cudenac. https://paulcudenec.substack.com/