I must have been around 15 years old when I first realised that there was something deeply wrong with modern society.

A few years later I had noticed that this situation was getting markedly worse and, a bit later still, it dawned on me that, in addition, the rate of this decline was rapidly accelerating!

Of course, I initially had no idea why things were so fundamentally out of kilter and sliding ever further towards disaster.

But I eventually understood that the problem did not come from outside England – from Americanisation, the threat of Soviet Communism or European centralisation, as people assumed – but was largely hosted in the capital city in whose suburbs I had grown up.

In recent years I have also become increasingly aware of the spiritual nature of this malaise.

The financial-industrial imperial beast has a black heart.

It not only works hard to eradicate all true spirit and soul from our lives, but it also infects us with its perverted anti-spirit.

I have come to see that it is nothing less than a manifestation of evil – an evil that will end up destroying humankind and our world, if we do not defeat it.

Our struggle against this malignant entity must therefore necessarily be a spiritual one and we must seek to arm ourselves appropriately to fight on that level.

But where can we do that, when organised religions offer us so little inspiration and appear to be yet more fronts for the same global Leviathan?

One very useful contribution comes from American poet, philosopher and theologian Michael Martin, in a book he edited in 2016 entitled The Heavenly Country: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Poetry, and Critical Essays on Sophiology, [1] with which I have just caught up.

There is a lot to digest in this work and so I will be publishing my thoughts in the form of three essays, starting with this one, plus a poetic footnote to appropriately complement the trinity with a fourth element.

After this avalanche of articles over the coming days, I will be taking a break, thus allowing anyone who so desires plenty of time to take all of this in.

“So what on earth is sophiology?” I hear some of you asking.

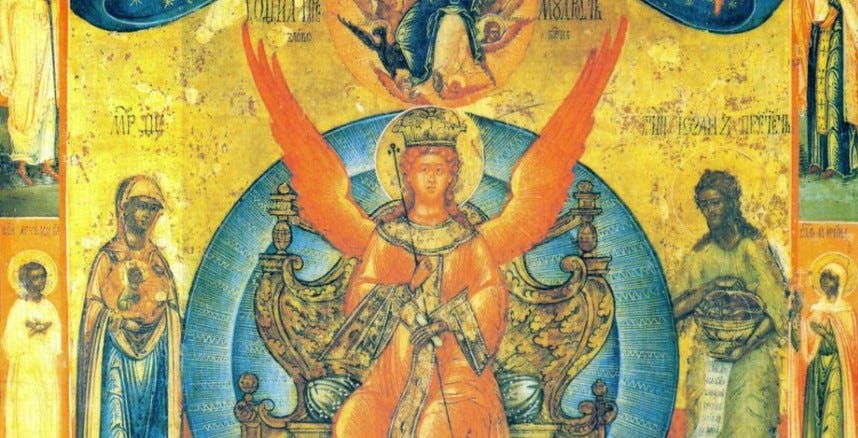

Well, it’s the study of Sophia, a religious character or metaphysical metaphor broadly representing divine wisdom and the presence and beauty of that wisdom in our world and in our hearts.

The notion of Sophia was not unknown to me before reading this compilation or indeed W.D. James’ review of another book on the subject which we published on the Winter Oak site earlier this year. [2]

In fact, she makes cameo appearances in two of my own books.

In The Fakir of Florence, a somewhat mystical novel from 2016, I depict a Sophia who is, at one and the same time, a 15th century nun and a 21st century woman who works in the café that now stands in the courtyard of the former convent where her counterpart lived. [3]

As Sister Sophia she writes down the wisdom of the celebrated fakir and as mysterious waitress Sofia she initially helps the central character in the novel to translate into English an apparently historical book about that fakir, before eventually admitting that this was really a fictional account, originally written in English, that she had herself translated into Italian.

Yes, I know, it’s a bit complicated! But the core idea is that she is a presence, both real and other-worldly, involved in passing on metaphysical wisdom.

My 2017 book The Green One presents the multi-faceted entity of that name, which is both “the agent by which life is created and nurtured” and our awareness, in our mythology and religion, of that agent and of its overriding importance. [4]

I have this character declare: “I am also Sophia, whether regarded as the Wisdom of God or as the Goddess of Wisdom, and I am Sapienta, the universal knowledge that binds the cosmos together”. [5]

I add: “Any true lover of Sophia understands that she is the beginning, the foundation, the source of experience, the self-knowing and self-creating of Natura naturans channelled by human beings who have grasped their own role and reality within that larger world”. [6]

Having read Martin’s compilation, I don’t think my equation of Sophia with The Green One is misplaced.

Just as the twelfth-century Christian philosopher Hildegard von Bingen uses the term viriditas – drawn from the Latin words for “green” and “truth” – to describe the sacred creative power of life, [7] so does one of Martin’s selected primary texts evoke the colour green in a spiritual context.

Thomas Vaughan, a mystic Anglican priest, introduces in Lumen de Lumine (1651) a version of Sophia called Thalia, whom he has announce: “I have many Names, but my best and dearest is Thalia: for I am alwaies green, and I shall never wither.” [8]

One of the academics contributing to the book, Bruce V. Foltz, argues that some versions of the character could be seen as “highly suspect” for Christians due to the identification of the Gnostic Sophia with Isis and Persephone. [9]

But Martin, the editor, insists on Sophia’s place in the Christian tradition by including a selection of references to her from the Old Testament’s Books of Wisdom.

There we read that “she is a vapour of the power of God… the brightness of eternal light, and the unspotted mirror of God’s majesty, and the image of his goodness”. [10]

Sophia is sometimes imagined as a goddess and sometimes as an aspect of God – a fourth note in the divine chord of the Holy Trinity.

She is the “revealer of the Mysteries and hidden wonders of the Deity… enlightener of the still Eternity” of 17th century mystic John Pordage [11] and the “Wild air, world-mothering air” of 20th century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. [12]

For Pordage’s English contemporary Thomas Bromley she is “the first and Chief Spouse of Christ” and “the Womb of Wisdom”, [13] while for 20th century Russian esotericist Valentin Tomberg she is “the ‘Virgin of Light’ of the Pistis Sophia, the Wisdom sung of by Solomon, the Shekinah of the Cabbala, the Mother, the Virgin, the pure celestial Mary”. [14]

A couple of Sophia’s admirers featured in the book claim to have actually encountered her in visions.

Jane Lead, another 17th century English mystic, describes her experience in her book A Fountain of Gardens.

She writes: “There came upon me an overshadowing bright Cloud, and in the midst of it the Figure of a Woman, most richly adorned with transparent Gold, her Hair hanging down, and her Face as the terrible Crystal for brightness, but her Countenance was sweet and mild.

“At which sight I was somewhat amazed, but immediately this Voice came, saying, Behold I am God’s Eternal Virgin-Wisdom, whom thou hast been enquiring after; I am to unseal the Treasures of God’s deep Wisdom unto thee, and will be as Rebecca was unto Jacob, a true Natural Mother; for out of my Womb thou shalt be brought forth after the manner of a Spirit, Conceived and Born again: this thou shalt know by a New Motion of Life, stirring and giving a restlessness, till Wisdom be born within the inward parts of thy soul”. [15]

The other writer who tells of a real encounter is Vladimir Solovyov, whose work during the 19th century established sophiology as a feature of the Russian Orthodox Church.

He never explicitly names the figure whom he says he met on three occasions during his life, preferring to refer to her as his “Eternal Friend”. [16]

He sees Sophia as the “guardian angel of the world” and the agent of “pan-unity”, [17] representing the “world soul” and “archetypal humankind”. [18]

Most writers describe her more as a concept than as a being one could ever hope to meet.

Pavel Florensky, who continued and developed Solovyov’s thinking into the 20th century, declares: “Sophia is essential beauty in all of creation”. [19]

“Sophia is the Great Root by which creation goes into the intra-Trinitarian Life and through which it receives Life Eternal from the One Source of Life”. [20]

“She is the Eternal Bride of the Word of God”, perceived as “the spark of the eternal dignity of the person and as the image of God in man”. [21]

His contemporary, the Russian Orthodox priest, philosopher and theologian Sergei Bulgakov, is evidently thinking along similar lines when he writes: “The divine Sophia, as the revelation of the Logos, is the all-embracing unity, which contains within itself all the fullness of the world of ideas… In Sophia the fullness of ideal forms contained in the Word is reflected in creation”. [22]

For 20th century American Trappist monk and theologian Thomas Merton, Sophia is “the feminine principle in the world”. [23]

He explains: “Sophia is God’s sharing of Himself with creatures. His outpouring, and the Love by which He is given and known, held and loved… She is life as communion, life as thanksgiving, life as praise, life as festival, life as glory”. [24]

“There is in all visible things an invisible fecundity, a dimmed Light, a meek namelessness, a hidden wholeness. This mysterious Unity and Integrity is Wisdom, the Mother of all, Natura naturans“. [25]

Outpouring! Glory! World-mothering air!

I feel that the very language of these descriptions and definitions strikes a blow for our resistance – even without looking further into the implications of Sophia’s presence for our understanding of nature and spirit, as I will be doing in the following essay.

The bureaucrats, banksters and brainwashers of the dark enslaving empire are incapable of thinking in this way, of rising to these heights, of reaching down to these inner depths of love.

Their inverted faith is in artifice, deadness and destruction – the world they have manufactured is thus a flattened-out one, a reduced one, a digitalised, sterilised, commodified one – a world stripped bare of both authenticity and grace.

They are certainly masters on their own lowly level of material reality, given their near-total possession of global wealth and the associated physical power – we will never defeat them by fighting purely on that terrain.

But there is another dimension in which we can take them on, a dimension in which their material superiority is transposed into spiritual inferiority, where their attachment to evil becomes a fatal weakness.

It is in this dimension – the dimension of the Great Root, the world soul and Life Eternal – that we can bring them down.

As author and theologian Aaron Riches puts it in his contribution to The Heavenly Country: “Sophia is best understood, then, not as a doctrine but as a liminal reality that can only be approached or seen in the most aesthetic of ways.

“Sophia is apprehended, not with the rigor of the scientific lens, but with the eyes of the heart that senses her and feels she is at the deepest mystery of reality”. [26]

[1] The Heavenly Country: An Anthology of Primary Sources, Poetry, and Critical Essays on Sophiology, edited by Michael Martin (Kettering, Ohio: Angelico Press/Sophia Perennis, 2016).

[2] W.D. James, ‘Immanent Sophia’. https://winteroak.org.uk/2024/05/20/immanent-sophia/

[3] Paul Cudenec, The Fakir of Florence: A novel in three layers (Sussex: Winter Oak, 2016).

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/the-fakir-of-florence-w-1.pdf

[4] Paul Cudenec, The Green One (Sussex, Winter Oak, 2017).

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/the-green-one-1.pdf

[5] Cudenec, The Green One, p. 181.

[6] Cudenec, The Green One, p. 183.

[7] Cudenec, The Green One, p. 148.

[8] Thomas Vaughan, ‘Lumen de Lumine’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 49.

[9] Bruce V. Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom: How (Not) to Speak of Sophia’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 367.

[10] ‘The Book of Wisdom’ 7: 25-26, in The Heavenly Country, p. 14.

[11] John Pordage, ‘Theologia Mystica, or The Mystic Divinitie of the Aeternal Invisibles’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 60.

[12] Gerard Manley Hopkins, ‘The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe’, first line, cit. Michael Martin, ‘The Poetic of Sophia’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 397.

[13] Thomas Bromley, ‘The Way to the Sabbath of Rest or the Soul’s Progress in the Work of the New Birth’, in The Heavenly Country, pp. 66-67.

[14] Valentin Tomberg, ‘Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 166.

[15] Jane Lead, ‘A Fountain of Gardens’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 73.

[16] The Heavenly Country, p. 109.

[17] The Heavenly Country, p. 110.

[18] Vladimir Solovyov, ‘Sobranie sochinenii’, ed. S.M. Solovyov and E.L. Radlov (Sankt-Petersburg, 1911-14), 3:140, cit. Robert F. Slesinski, ‘Russian sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 330.

[19] Pavel Florensky, ‘Celestial Signs’ in Beyond Vision: Essays on the Perception of Art, ed. Nicolette Misler (London: Reaktion Books, 2002), p. 254, cit. Foltz, ‘Nature and Divine Wisdom’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 366.

[20] Pavel Florensky, ‘The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 118.

[21] Florensky, ‘The Pillar and Ground of the Truth’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 120.

[22] Sergei Bulgakov, ‘Sophia, the Wisdom of God: An Outline of Sophiology’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 123.

[23] Thomas Merton, ‘Hagia Sophia’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 261.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Merton, ‘Hagia Sophia’, in The Heavenly Country, p. 258.

[26] Aaron Riches, ‘Theotokos: Sophiology and Christological Overdetermination of the Secular’, in The Heavenly Country, pp. 273-74.

Source: https://paulcudenec.substack.com/p/the-spirit-of-sophia-wild-air-and

Article courtesy of Paul Cudenac. https://paulcudenec.substack.com/