Something is smelling decidedly ‘off’ in today’s world, with nauseating levels of corruption, mass murder, lies, hypocrisy and repression. These three essays are based on three books I happen to have recently read, each of which provides fascinating but necessarily limited insights into the reality of contemporary society. Placed alongside each other, however, they can help us to identify the source of the odour.

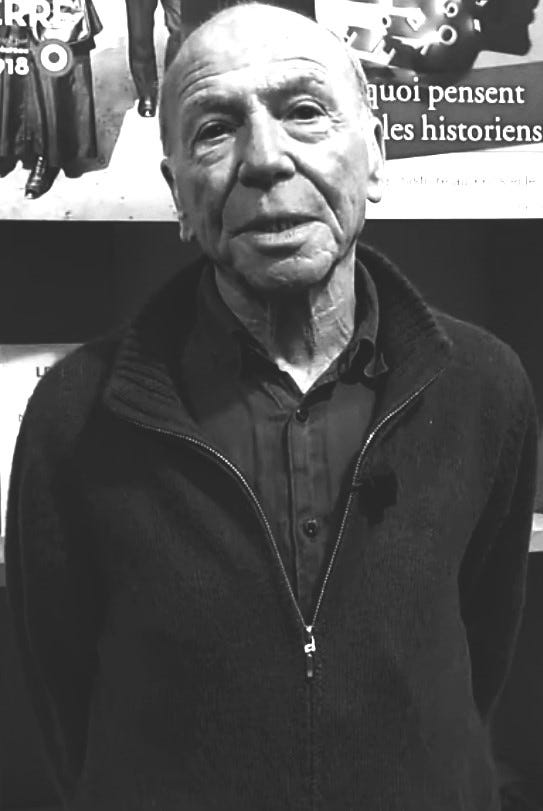

Eric Hazan, the French writer and publisher who died this summer at the age of 88, goes out of his way in his 2006 book LQR: La propagande du quotidien (‘LQR: Everyday Propaganda’) to insist that he is “obviously not equating neoliberalism with Nazism”. [1]

This is a rather puzzling thing for him to have written, since not only is neoliberalism very similar to Nazism and Fascism, as I have often pointed out, but this fact is also strongly confirmed by his book!

Moreover, the equation that he denies making even lies behind the book’s title, as he explains in the opening pages.

A German-Jewish academic Victor Klemperer kept note of the newspeak rolled out by the Hitler regime and in 1947 published his observations, using the term LTI, Lingua Tertii Imperii, Language of the Third Reich, to describe the phenomenon. [2]

Hazan (pictured) thus uses LQR, Lingua Quintae Republicae, Language of the Fifth Republic, to refer to the newspeak of contemporary (neoliberal) France.

The notable continuity between Nazi Germany and today’s “democratic” world is something I have mentioned on a number of occasions.

In 2021, in Fascism Rebranded, I discussed Johann Chapoutot’s 2020 revelations about a corporate Management Academy in Germany that was run from 1956 by a certain Reinhard Höhn, who had been a prominent protégé of Heinrich Himmler and a shining light of the SS. [3]

The post-war continuity was not just in the personnel – Höhn was not the only Nazi involved – but also in the authoritarian industrial mindset behind both National Socialism and business management.

As Chapoutot writes: “It transforms each person into a thing (res), an object, which must be useful in order to have the right to live and exist. The Germanic individual becomes a tool, a raw material (Menschenmaterial) and a factor – a factor of production, of growth, of prosperity”. [4]

Then in 2023 I pointed out how Emmanuel Macron’s government in France was intent on replacing “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” with the new slogan of “Work, Order and Progress”.

I remarked: “Try that out in German and see how it feels: ‘Arbeit, Ordnung, Fortschritt’. Hmmm…” [5]

The similarities in outlook and language keep cropping up. Earlier this year, a pro-government journalist said on French TV that “conspiracy theorists” were like “cockroaches” that had to be “got rid of”. [6]

For some years now, the French state has been using the strange term “dérives sectaires” – “sectarian excesses” – to describe thinking it doesn’t like, such as that of those very same “conspiracy theorists”. [7]

Where did they get this term from? It is a striking coincidence that the Nazi party in Germany also described dissident opinion as “sectarian” and staged training programmes for state employees so as to steer them away from ideas deemed unacceptable, including those of the anti-industrialist Ludwig Klages. [8]

In Klemperer’s book, he says that the Third Reich forged only a very few new words, but rather “changed the value of words and their frequency… subjected language to its terrible system, used it as its most powerful, public and secret means of propaganda”. [9]

Hazan writes that the contemporary French equivalent of this Nazi language relies on people not noticing that it is being deployed: “Above all else, it must not be seen for what it is”. [10]

He says it “is managing to spread without anyone, or hardly anyone, apparently noticing its advance”, hence his attempt “to identify and decipher this new version of the banality of evil”. [11]

Some of the examples he gives are specific to France, but others will be familiar to those living in the English-speaking world.

“Governance” is used instead of “government”; [12] “equity” instead of “equality”; [13] “reform” describes any acceleration of neoliberal “modernisation”, [14] while attacking an enemy for no good reason is a “pre-emptive” strike [15] aimed at ensuring “security”. [16]

There is, of course, “zero tolerance” for any challenge to “l’ordre républicain” [17] – known elsewhere as “law and order” or “the rule of law” – and, as we have noted, such a necessary companion to “work” and “progress”.

And no greater fear stalks the nightmares of a LQR-speaker than “the end of authority”. [18]

The parallels which Hazan finds are not just with Nazism but also with Soviet Communism, a slightly different model of 20th century industrial-authoritarianism.

He quotes one Vadim Zagladine as writing in 1989: “According to current Soviet thinking, security can only be assured through the joint efforts of all members of the global community”. [19]

That’s a turn of phrase that could have come straight out of Davos!

And Hazan notes the curiously close relationship between “neoliberal theories of ‘human capital’” [20] and the pronouncements of Stalin, who declared in 1931: “We must finally understand that of all the precious capital in the world, the most precious capital, the most decisive capital, is human beings”. [21]

For reasons which will quickly become clear, the language of the Fifth Republic seems to stigmatise one ethnic group in particular, using terms such as “arabo-musulman” [22] and “islamiste” – the latter, unlike “islamique“, having “the advantage of rhyming with terroriste“, as Hazan observes. [23]

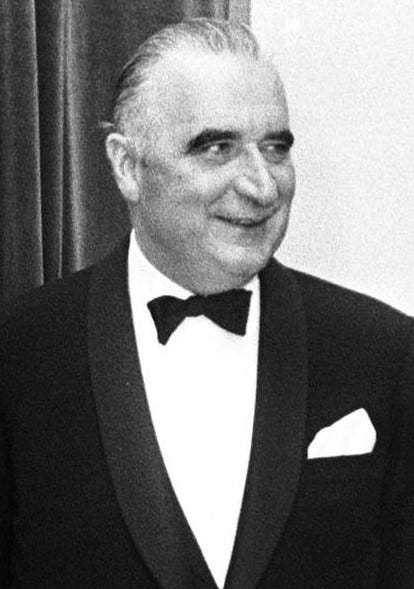

These people represent a threat that has to be “eradicated” (according to academic Gilles Kepel) and the places where they live “jet cleaned”, as former president Nicolas Sarkozy (pictured) put it. [24]

Hazan records that one of the after-effects of 9/11 was a change in the language used in France.

“Hatred of Islam was now being expressed in social circles, reviews and institutions that one would have imagined impervious to racism, or at least to its open expression”. [25]

As this taboo was lifted, others were imposed. Hazan cites one French journalist’s 2004 warning that criticism of neoliberal George W. Bush indicated a “resurgence of Americanophobia”, [26] while “expert” Alexandre Adler insisted that same year that “anti-Americanism is a fascistic emotion which in fact has an affinity with the ‘Muslim fascism’ propagated by the islamists”. [27]

Needless to say (particularly for anyone who has read the first essay in this short series), the greatest outpourings of outrage are reserved for instances of alleged “anti-semitism”, which somehow seems to be perpetually on the rise.

Hazan records the melodramatic reaction of the political class to a 2004 fire at a Jewish social centre in Paris, which later turned out to have set by a Jewish man with mental health problems. [28]

Jacques Chirac, president at the time, expressed his “profound indignation”, “strongly” condemned “this unspeakable act” and insisted on the “absolute determination” of the authorities to track down the culprits. Presidential determination is usually either “absolute” or “unwavering”, remarks Hazan. [29]

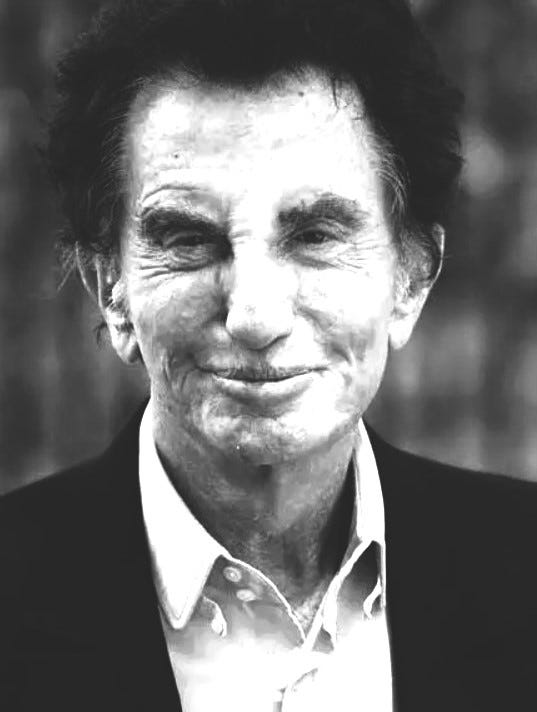

Bertrand Delanoë, Mayor of Paris, warned of a “nasty dangerous atmosphere”, while politician Jack Lang (pictured) called for “action” instead of “fine words and crocodile tears”, although, as Hazan points out, he did not indicate what kind of action he had in mind. [30].

Hazan, who was himself Jewish, also points to a book, nearly 1,000 pages long, on the subject of “planetary Judeophobia”, written by Pierre-André Taguieff in a totalitarian style he regards as typical of LQT.

“He is not content with just insulting his enemies; they are exposed to public condemnation in a work whose 15-page index reads like a proscription list”. [31]

Hazan also does not shy away from making a key connection, related to the meaning of “terrorism”.

He notes that French TV news described a 2004 Palestinian resistance attack on an Israeli fort in Rafah, in the south of Gaza, as a “terrorist attack”. [32]

This, he says, mirrored the application of the same term to the wartime French Resistance by Philippe Henriot, Secretary of State for Information in Petain’s Nazi-collaborating Vichy regime. [33]

Henriot was assassinated in April 1944 and the day after his funeral a statement was printed in Combats, the journal of the pro-Nazi paramilitary police force, the Milice.

It said: “Philippe Henriot, we renew our promise to you to fight to win, to rid France of these gangs of looters which are terrorising our provinces”. [34]

An obfuscation, nay inversion, of the relative moral standing between the system and its opponents is central to the language of contemporary power.

In a society run by “the politico-financial oligarchy”, [35] says Hazan, the official vocabulary thus never speaks of profit, but of a “return on investments” [36] and, as he explains, there can be no room for old-fashioned notions such as exploitation or oppression.

“These words would effectively imply that there is such a thing as exploiters and oppressors, which is a bad fit with the announced end of class relationships.

“However, a way had to be found of designating those who live in misery, now too numerous to be simply rendered invisible.

“The experts have found the name: they are the excluded. The replacement of the exploited by the excluded is an excellent move for the proponents of consensual pacification, since there are no identifiable excluders to be the modern equivalents of the exploiters of the proletariat”. [37]

Contemporary non-exploiters in the business and financial world are presented to the public as “sensitive souls” [38] with “noble sentiments”. [39]

Hazan illustrates this with regard to the way the media presented the 2004 arrival of financier Edouard de Rothschild (pictured) as leading shareholder of Libération, a supposedly “left-wing” daily newspaper founded by Jean-Paul Sartre in 1971.

One newspaper editorial gushed: “His investment in Libération will be his first step as a patrician concerned about public debate and for the irreplaceable role of the daily press”. [40]

Rothschild himself has declared: “At certain moments one has to know how to charm; and at others to impose oneself”. [41]

Hazan remarks that this kind of language “presents ‘the ruling elite’ as a sort of collective good papa, severe but benevolent. Firmly determined to uphold the rule of justice for the happiness of the population”. [42]

Sometimes the most important insights into any subject matter turn up at the intersection of two different sources.

This is the case with the word “ensemble” – together – which Hazan presents as part of his Language of the Fifth Republic, deployed everywhere in an apparent bid to give the impression of national unity and thus to maintain order.

In official messaging and advertising alike, people are urged to keep the pavements clean ensemble, to take care ensemble on the Paris Metro, to respect the environment ensemble. [43]

There are also warnings that “extremists” – including those ever-lurking “anti-semites” – are threatening democracy and people’s capacity to live ensemble. [44]

In Jacob Cohen’s “fictional” account of Zionist influence on French society, which I wrote about in the first of these essays, he describes an advertising campaign featuring the slogan “Ensemble, éclairons le monde” – ‘Together, let’s light up the world’ – with a photo of a Menorah (seven-branched candelabrum) and the name of the Jewish religious festival Hanukkah.

The purpose of this is explained thus: “Hanukkah must become a familiar notion. A universal message of peace, symbolising freedom and linked to the history of the Jewish people. The identification with Israel will happen naturally”. [45]

A decade after both Cohen and Hazan wrote about the political deployment of the word ensemble, it became, in 2021, the name of the coalition of parties supporting President Macron, [46] a former Rothschild banker [47] who is said to still be very close to the famous Jewish family.

Hazan says that LQR first appeared “during the course of the 1960s, during gaullo-pompidouism [the governments of General de Gaulle and Georges Pompidou], that brutal modernisation of traditional French capitalism”. [48]

As I explained in Enemies of the People, Pompidou was the director general of the Banque Rothschild, who initially ran de Gaulle’s staff office for six months. [49]

There he revised the constitution so that the Fifth Republic of 1958 (that lent LQR its name) would allow more presidential power over elected representatives – a power which has also been very useful for Macron in recent years.

Pompidou returned to the Rothschild bank, before going back into politics as de Gaulle’s second Prime Minister between 1962 and 1968, then becoming president from 1969 until his death in 1974.

During that period there was much social unrest in France, including the famous uprising of 1968.

One group, La Gauche Prolétarienne (The Proletarian Left), formed in 1970, was particularly known for its direct action attacks (“terrorism” for some) on the ruling class and the ultra-rich.

Its theoretical journal, J’Accuse, included among its contributors and editors André Glucksmann, Michel Foucault, Jean-Luc Godard, Gilles Deleuze, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Explains journalist and author Francis Wheen: “They also published a newspaper, La Cause du Peuple, and when its editor was arrested Sartre himself took over – though his efforts went largely unnoticed, since the police confiscated every issue.

“Only two years after les évenements of May 1968, the Pompidou government was taking no risks: it also banned the Cuban journal Tricontinental, the left-wing review Le Point and Carlos Marighella’s Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla“. [50]

Is it mere coincidence that the fascistic Pompidou (pictured) was, like Macron, a career Rothschild banker?

Is it coincidental that, as I related in Enemies of the People, the Rothschilds funded, via their Wall Street fronts, Soviet Communism, Italian Fascism and German Nazism, with the aim of advancing their industrial-authoritarian agenda?

Hazan’s book, especially when taken together with Cohen’s, paints a disturbing portrait of the hidden reality of contemporary French society.

And, of course, that reality is mirrored in other countries, as will be confirmed in the third and last of these insights.

See also:

The stench of the system: sayanim

[1] Eric Hazan, LQR: La Propagande du quotidien (Paris: Raisons d’Agir Editions, 2006), p. 18. All translations are my own. Thanks to Karim for the recommendation!

[2] Hazan, p. 11.

[3] Paul Cudenec, Fascism Rebranded: Exposing the Great Reset (2021), pp. 280-84.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/fascism-rebranded23web.pdf

[4] Johann Chapoutot, Libres d’Obéir: le management du nazisme à aujourd’hui (Paris: Gallimard, 2020), pp. 65-66.

[5] Paul Cudenec, Converging Against the Criminocrats: Essays and Talks for the New International Resistance (2023), p. 73.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/convergingagainstthe-criminocratsweb-1.pdf

[6] https://juste-milieu.fr/alba-ventura-et-les-cafards-complotistes-que-fait-larcom/

[7] https://www.miviludes.interieur.gouv.fr/quest-ce-quune-d%C3%A9rive-sectaire

[8] Paul Cudenec, ‘Life philosophy: beyond left and right’.

https://winteroak.org.uk/2024/10/14/life-philosophy-beyond-left-and-right/

[9] Victor Klemperer, LTI, la langue du IIIe Reich, carnets d’un philologue, trad. Elisabth Guillot (Paris: Albin Michel, 1996), pp. 38-39, cit. Hazan, p. 12.

[10] Hazan, p. 121.

[11] Hazan, p. 14.

[12] Hazan, p. 29.

[13] Hazan, p. 33.

[14] Hazan, p. 31.

[15] Hazan, p. 29.

[16] Hazan, p. 18.

[17] Hazan, p. 76.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Pour la restructuration et l’humanisation des relations internationales (Moscow: Novosti, 1989), p. 80, cit. Hazan, p. 37.

[20] Hazan, p. 44.

[21] https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Joseph_Stalin

[22] Hazan, p. 84.

[23] Hazan, p. 87.

[24] Hazan, p. 88.

[25] Hazan, p. 90.

[26] Hazan, p. 93.

[27] Hazan, p. 94.

[28] Hazan, p. 79.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Hazan, p. 96.

[32] Hazan, p. 39.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Jacques Delperrié de Bayac, Histoire de la Milice (Paris: Fayard, 1969), p. 503. cit. Hazan, pp. 39-40.

[35] Hazan, p. 20.

[36] Hazan, p. 29.

[37] Hazan, p. 107.

[38] Hazan, p. 80.

[39] Hazan, p. 75.

[40] Hazan, p. 75 FN.

[41] Hazan, p. 75.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Hazan, p. 111.

[44] Hazan, p. 111 FN.

[45] Jacob Cohen, Le Printempts des sayanim: Récit (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2010), p. 126.

[46] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ensemble_pour_la_R%C3%A9publique_(France)

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Macron

[48] p. 12.

[49] Paul Cudenec, *Enemies of the People: The Rothschilds and their corrupt global empire (2022), pp. 44-45.

https://winteroak.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/enemiesofthepeopleol.pdf

[50] Francis Wheen, *Strange Days Indeed: The Golden Age of Paranoia* (London: Fourth Estate, 2010), p. 88.

Source: https://paulcudenec.substack.com/p/the-stench-of-the-system-propaganda

Article courtesy of Paul Cudenac. https://paulcudenec.substack.com/